Everything patients need to know about Aduhelm (aducanumab) | New Alzheimer's Medicine

Last updated: 15 March 2022

You can legally access new medicines, even if they are not approved in your country.

Learn howArticle reviewed by Dr. Jan de Witt

On the 7th of June 2021, FDA approved aducanumab (produced under the trade name “Aduhelm") for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease, raising the hopes of millions of Alzheimer’s patients and their families around the world while experts voiced their concerns over the decision.

Aduhelm is the first medicine for Alzheimer’s disease to be approved by the FDA in 18 years This medicine claims, according to the results published, to be capable of slowing the progression of Alzheimer’s disease itself, rather than alleviating its symptoms.

The FDA’s decision to approve the medicine has been fraught with controversy. Nevertheless, Biogen, the manufacturer of Aduhelm, expects to start shipping Aduhelm to more than 900 healthcare centers in the United States by the end of June 2021.

Aduhelm is currently available for suitable patients outside of the United States on a compassionate use or a named patient basis. Learn more by jumping to the section “Accessing Aduhelm outside of the United States”.

Alzheimer’s disease: one of the 21st century’s major social, medical and economic crises

Alzheimer’s disease is a degenerative brain disorder that today affects over 40 million people around the world and is the most common cause of dementia. Believed for many years to be a normal part of aging, Alzheimer’s disease is now recognised as a condition with serious healthcare, economic, and social impacts.

Researchers do not yet fully understand what causes Alzheimer’s disease, but it is believed to be caused by a combination of factors, such as:

- Aging: Alzheimer’s is most often diagnosed after age 65 (late-onset Alzheimer’s disease). About one third of people aged 85 and over have Alzheimer’s disease. Changes in the brain related to aging can contribute to developing the condition.

- Family history: Having a first degree family member with Alzheimer’s increases the risk of a person developing the disease. Scientists believe that a genetic predisposition can cause early-onset Alzheimer’s, which occurs in people in their 30s to mid-60s. Only 10% of Alzheimer’s patients have the early-onset form of the disease.

- Other factors: Scientists have found links between cognitive decline and heart disease, as well as diabetes and obesity. The strongest evidence links brain health to heart health. Head injuries have also been linked to an increased risk of Alzheimer’s as they can trigger the formation of amyloid plaques. People with Down’s syndrome, in which an extra chromosome dictates the genetic coding for a type of amyloid protein linked to Alzheimer’s, are at increased risk as well.

The majority of people with Alzheimer’s are diagnosed in the mild stage, when symptoms become more pronounced and the disease has already caused some brain damage, despite the fact that some symptoms start to appear even a decade before the diagnosis. Early symptoms may be disregarded by patients (often due to shame) or simply not noticed by doctors or family members. Patients have an average life expectancy of 3-11 years after diagnosis.

“In time, Mum forgot who I was”

Alzheimer’s disease has three different stages:

- Mild: In the first stages, patients experience memory loss such as forgetting important dates and events, frequently repeating questions, taking longer to complete daily tasks, constant trouble with finances, frequently misplacing items, and anxiety. (To learn more about how much memory loss is normal with aging, see this infographic by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)’s National Institute on Aging.)

- Moderate: As the disease progresses, patients have increased memory loss and confusion, difficulty with communication and reading, difficulty with routine tasks such as getting dressed, problems recognizing family and friends, paranoia, hallucinations, and wandering.

- Severe: Patients with severe Alzheimer’s experience an inability to communicate, weight loss, difficulty swallowing, and loss of bowel or bladder control. At this stage, patients are in bed most of the time and are entirely dependent on others for their care.

The hardships of Alzheimer’s patients are dire, as the disease impacts every aspect of their day to day lives. Below you can read a few stories by patients or by friends and family of patients.

Sandy, a former dentist and assistant professor at Harvard, spoke to CNN reporters about his realization that his forgetfulness had progressed to something worse: "’I am looking at a dental case file for an hour and a half,’ he recalls. ‘I'm reading it, it's in my brain. Then I would close the file and not remember literally anything about the case.’” Shortly after, he was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease.

Fred Walker, whose wife has been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, spoke to Alzheimer’s Research UK about his wife: “‘To use the telephone became beyond her capabilities. She couldn’t master all the buttons. The cooker was far too complex to understand and there was always the danger of her leaving the gas on. She found making a cup of tea too much and would get confused as to how much tea, milk and water was needed.’”

Alzheimer’s disease, when reaching the later stages and progressing into dementia, is described by Laury for Alzheimer’s Society:

“[...] we embarked on a new journey. One that involved 24-hour care, daily medication rounds, and Mum becoming utterly lost in the fog of her own mind. [...] It didn’t sink in until that point the full horror show that watching a loved one with this cruel, insidious disease actually entailed. [...] She began to hallucinate.”

everyone.org founder Sjaak Vink confirms and recognizes each and every of these descriptions. His mother was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in 2015.

It is a difficult road for patients and their loved ones — and the disease does not limit itself to impacting only their personal lives and the lives of their loved ones.

Pressure on carers, budgets and policy makers

Patients with Alzheimer’s require increasingly demanding care as their condition deteriorates, such as in-home care, night care, housekeeping services or nursing care; eventually, patients may need to live in assisted living facilities or nursing homes. The disease takes a heavy toll on the patient, on their family members (who often dedicate themselves to caring for the patient), and on their personal and the state’s budgets.

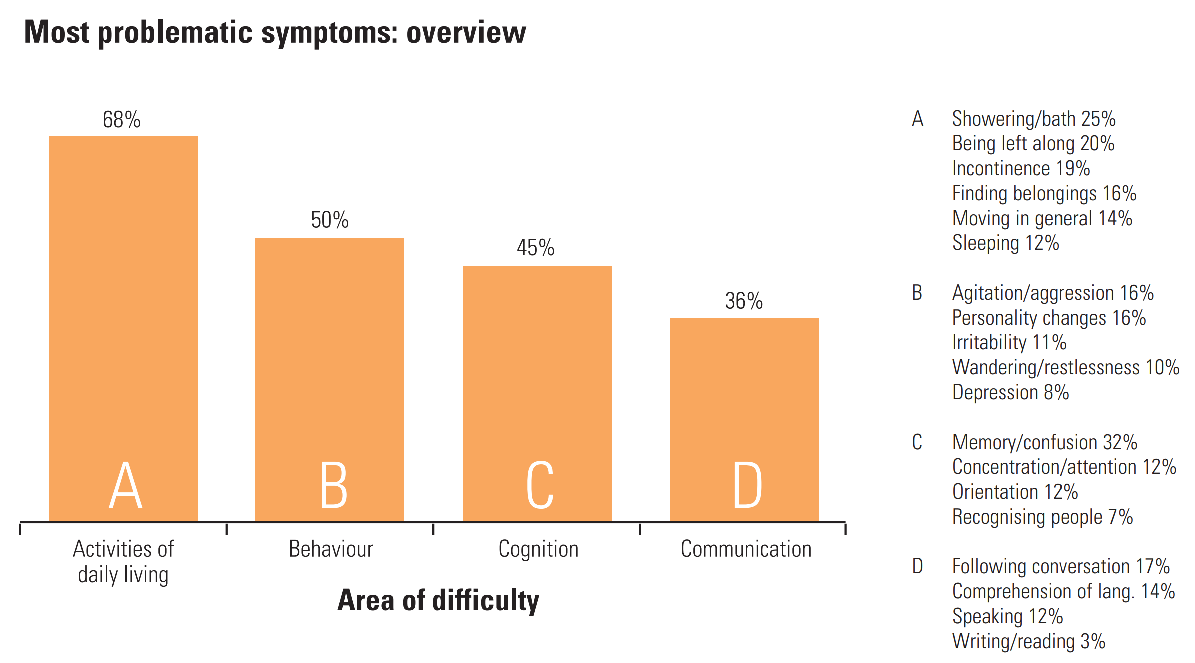

Family carers face a difficult mission when caring for their loved ones with Alzheimer’s disease. A survey found that 95% of family carers in the UK say it affected their physical or mental health, 69% reported feeling constantly exhausted, 64% felt anxious and 49% felt depressed.

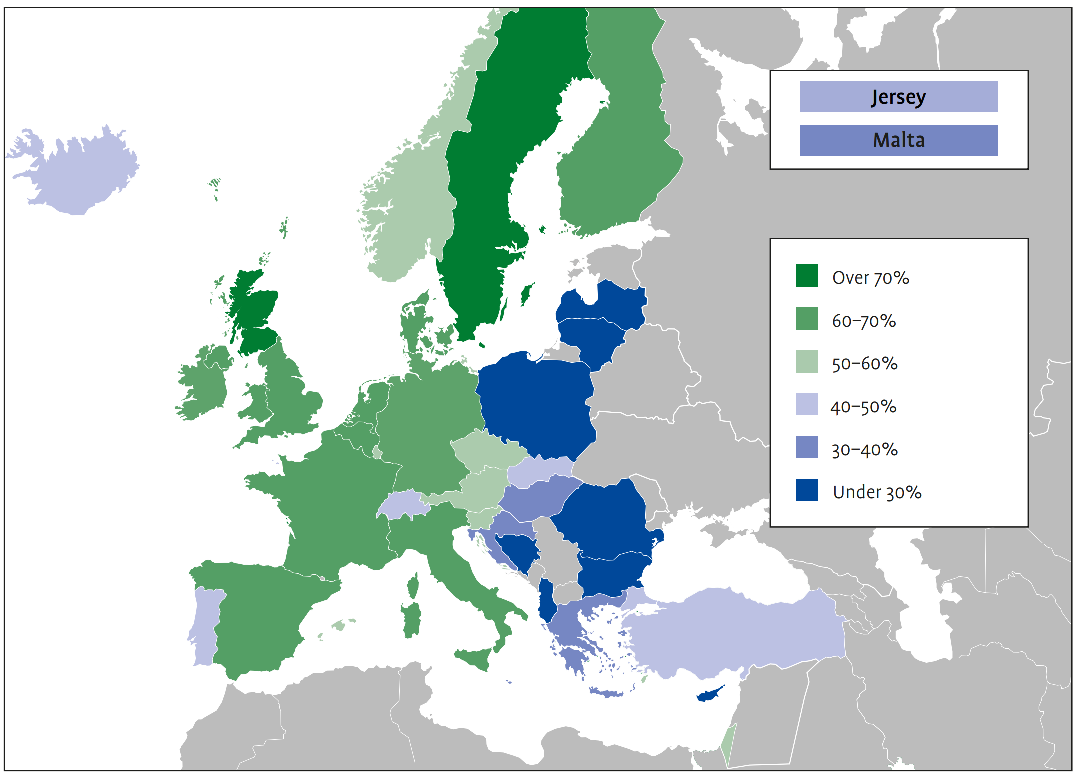

In Europe, Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia affect around 10 million people and the number is expected to increase to 14 million by 2030. The economic cost of dementia in Europe is estimated to increase to over €250 billion by 2030, with over 50% of this due to informal care costs. There is unequal access to care and treatment and, particularly in Eastern Europe, there is a lack of available support systems and social programs for Alzheimer’s patients and their carers.

In the United States, Alzheimer’s disease has recently entered the list of top 10 causes of death and is the only one in the top 10 with no known cure. It affects 6 million people in the US and the number is projected to increase to 12 million by 2050. By the end of 2021, the total national cost of caring for people living with Alzheimer’s and other dementias could reach $355 billion and is projected to reach $1.1 trillion by 2050.

This funding, as astronomical as it may seem, is necessary to offer patients adequate support and, as much as possible, a dignified life.

Due to the round the clock care required, especially in the later stages, patients with Alzheimer’s are particularly affected when their care is inadequate, which is the case in many countries or communities. In the UK alone, tens of thousands of people with dementia are admitted to the emergency room every year due to infections, falls and dehydration, which result from insufficient care. This further stresses national healthcare budgets.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Alzheimer’s patients have been severely hit and have suffered a high death toll due to age, other long-term health conditions and Alzheimer’s challenges themselves (e.g. memory problems and confusion which make patients struggle to follow guidelines that prevent COVID-19 infections).

Alzheimer’s patients in care homes have felt the damaging consequences in other ways as well. Due to insufficient care and enforced separation from their loved ones in order to keep them safe from COVID-19, the ensuing loneliness and isolation has further deteriorated their mental and physical health.

Effective treatments for the disease are needed to also stop the health and economic crises from reaching severe proportions.

Highlights in Alzheimer’s disease research

In 1910, Emil Kraepelin, a doctor in Germany, named the condition “Alzheimer's disease” after physician Alois Alzheimer, who discovered pathological features of presenile dementia in a patient with profound memory loss and worsening psychological changes. Research for treatments for Alzheimer’s disease only began in the late 1980s in the United States, but faced criticism as doctors still believed that Alzheimer’s was an inevitable consequence of aging.

In the United States in 1978, the National Institute on Aging (NIA) and the Alzheimer’s Association partnered with Pfizer and began the first clinical trial for a medicine that would treat symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease. The medicine was approved in 1993: Cognex (tacrine), according to the results published, improved cognitive abilities in some patients, but did not stop the disease from getting worse.

Over the next decade, six more medicines were approved, all for treating the cognitive symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease:

- Aricept (donepezil): for treating symptoms related to memory and thinking

- Razadyne (galantamine): for treating symptoms related to memory and thinking

- Exelon (rivastigmine): for treating symptoms related to memory and thinking

- Namenda (memantine): to improve memory, attention, reason, language

- Namzaric (memantine + donepezil): a combination of the above

- Belsomra (Suvorexant): for treating insomnia in Alzheimer’s patients

The last medicine to be approved for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease was approved in 2003. For decades, Alzheimer’s disease was considered a natural consequence of aging. Few resources were dedicated to finding a treatment, as there was a debate whether it was an actual disease. Over the past 20 years, however, researchers have dedicated ample resources to studying the disease and developing a treatment.

The lack of treatments for Alzheimer’s is not due to neglect on the side of pharma companies — the industry overall has invested billions into research. The company Eli Lilly alone has spent $4.2 billion over three decades trying to develop a successful medicine, and the United States National Institutes of Health (NIH) has spent more than $500 million a year in researching and developing treatments.

Since 2013, The United States Congress has tripled the NIH’s annual budget for Alzheimer's research funding and related dementias, reaching $3.1 billion in 2019.

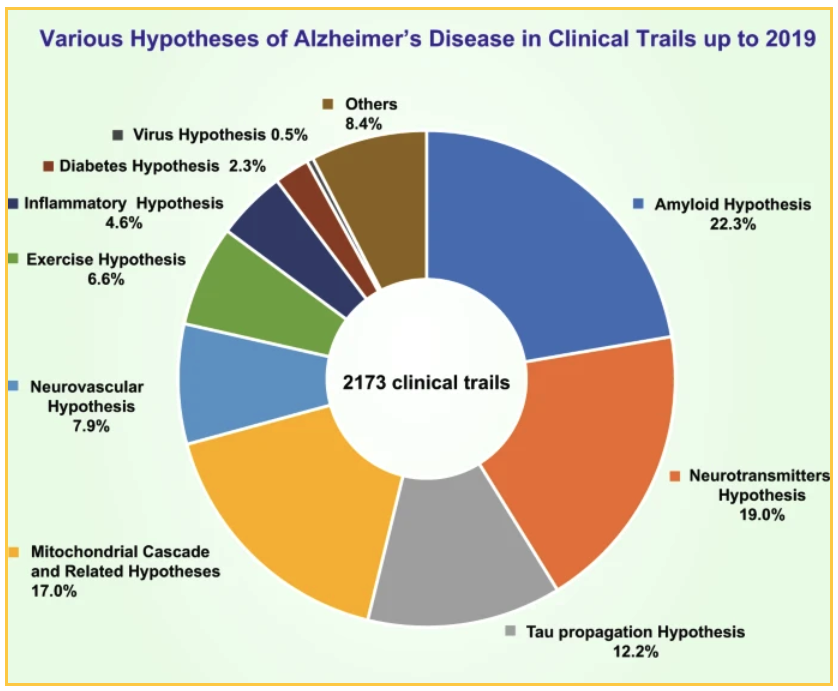

National and private funding has resulted in 2173 clinical trials that have been conducted by 2019 to test various theories. The top theories tested:

- 19% of trials focused on a neurotransmitter hypothesis

- 17.0% of trials tested a mitochondrial cascade hypothesis and other related hypotheses

- 12.7% tested the tau propagation hypothesis

The 22.3% of trials which target amyloid focus on different ways of reducing the plaque:

- Immune system-generated antibodies to beta-amyloid: “Active vaccines” which when injected into the body, trigger the immune system to produce antibodies to destroy beta-amyloid and reduce levels of beta-amyloid in the brain.

- Laboratory-produced antibodies to beta-amyloid: “Passive vaccines,” which are considered more effective and safer than trying to induce antibody production in the body.

- Decreasing beta-amyloid production: Some experimental treatments change the behavior of certain proteins that can prevent or reduce beta-amyloid production.

- Preventing beta-amyloid aggregation: Scientists are researching drugs that prevent the initial interactions between beta-amyloid and brain cells that lead to the death of the brain cell.

- Increasing beta-amyloid removal: Techniques such as mobilizing the immune system to attack the beta-amyloid or administering natural agents with anti-amyloid effects.

- Natural agents with anti-amyloid effects: Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) obtained from human blood donors contains natural antibodies that can reduce beta-amyloid levels.

What is Aduhelm (aducanumab-avwa)?

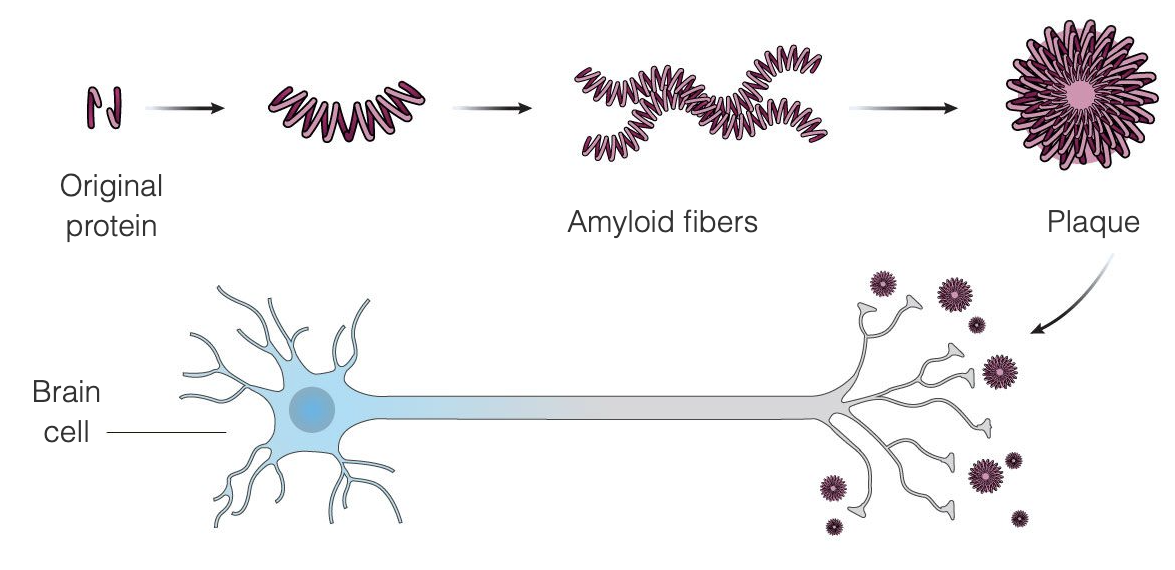

Aduhelm (aducanumab) is an anti-amyloid antibody indicated for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. It is designed to remove beta-amyloid plaques that form between brain cells in abnormal amounts in patients with Alzheimer’s disease, which lead to the death of the affected brain cells. The beta-amyloid was identified in 1984 and was quickly considered the main trigger for brain cell damage, while in 1986 the tau protein was identified, a key component of tangles and a second trigger of brain cell deterioration.

Aduhelm was developed by Biogen, Inc., a multinational biotechnology company based in Massachusetts, United States. Aduhelm is administered as a monthly injection.

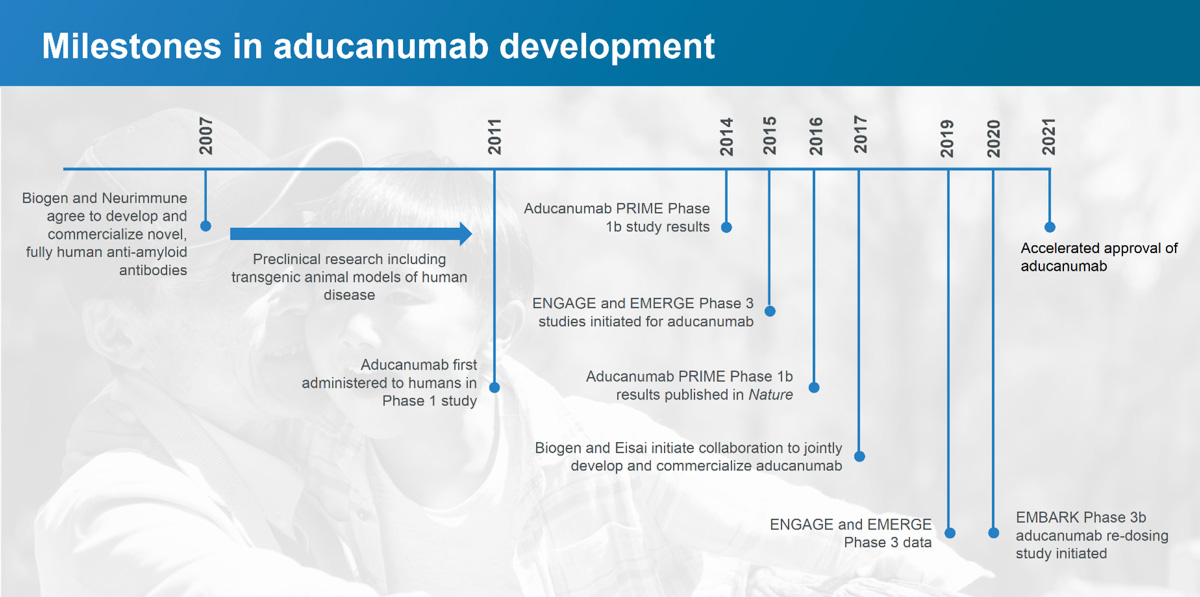

Aduhelm has a long history.

Swiss biotech company Neurimmune Therapeutics AG, in collaboration with the University of Zurich, identified the protective anti-amyloid antibodies in healthy elderly people and patients with slowly progressing dementia and led to the discovery of aducanumab, the active ingredient in Aduhelm. In patients with mild Alzheimer’s disease, one year of monthly intravenous infusions of aducanumab reduces amyloid plaque, which results in a slowing of cognitive decline.

Neurimmune licensed aducanumab for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease to Biogen in 2007 and works in collaboration with Biogen on its development.

How does Aduhelm work?

Alzheimer’s disease appears to be the result of the unusual accumulation in the brain of two proteins, beta-amyloid and tau. Beta-amyloid is a protein that is normally present in the brain that, in Alzheimer’s disease, clumps into amyloid plaques between brain cells — the amyloid theory states that these plaques damage and eventually kill the brain cells. Amyloid plaques seem to develop earlier in the disease, whereas tau tangles tend to appear later in the disease. Much of the research that has been conducted to find a treatment for Alzheimer’s disease has focused on removing amyloid plaques.

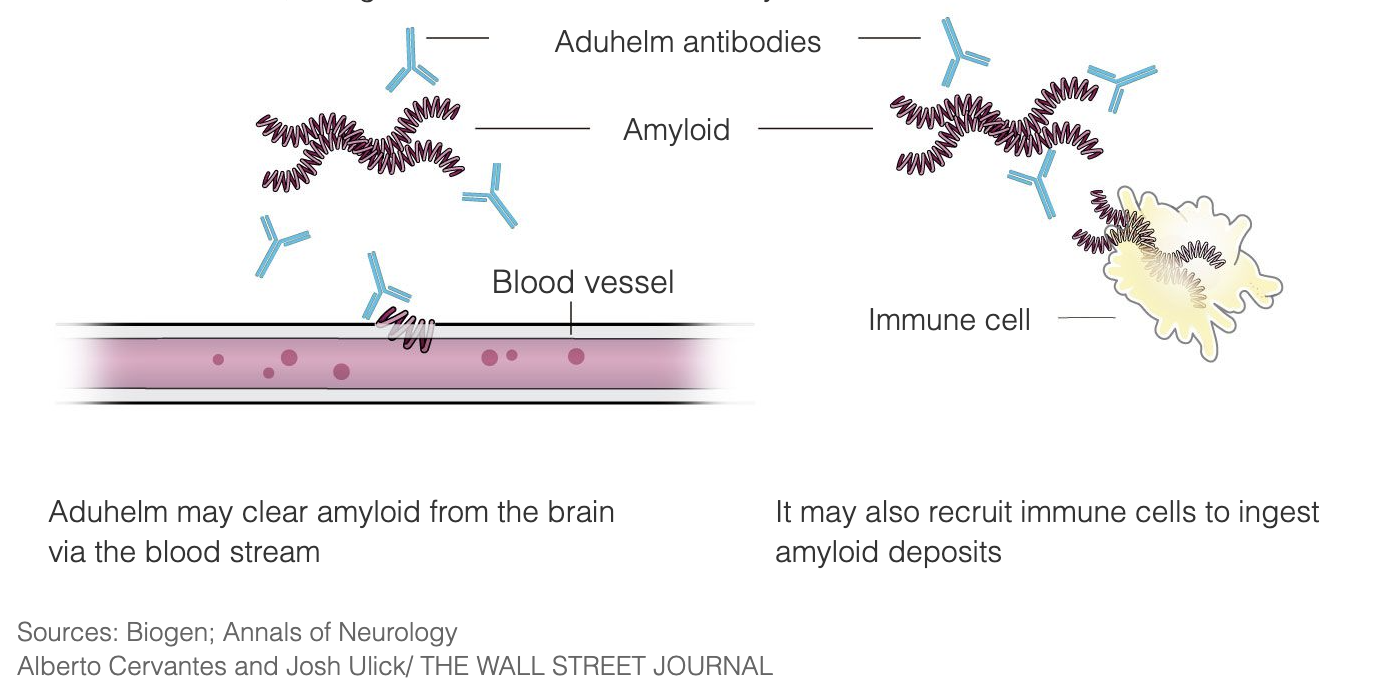

Aduhelm is designed to treat Alzheimer’s at the very early stages of the disease by binding to the amyloid plaques, thus triggering the immune system to destroy the plaques, seeing them as a foreign invader. The intent is that once the plaques are removed, the brain cells will stop dying and cognitive function will stop deteriorating. Aduhelm is using this mechanism with the aim of slowing down the progression of the disease, addressing particularly patients in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. Aduhelm does not reverse damage that has already been done.

Amyloid plaques have been a target of Alzheimer’s disease research and medicine development for 3 decades, and Aduhelm is one of such treatments that have been researched over the years.

“The Church of the Holy Amyloid”

Scientists do not yet agree on what causes Alzeimer’s disease, but they have certain theories. One of them is called “the amyloid hypothesis” and Aduhelm was developed on the assumption that this theory is correct.

The amyloid hypothesis states that amyloid plaques forming between brain cells causes the cells to die, which leads to cognitive decline. It is a long-standing theory that has never been universally accepted — and the failure thus far of the clinical trials that target amyloid plaques have emboldened its critics. Some call the group of supporters of the theory “the Church of the Holy Amyloid” due to their reluctance bordering on refusal to entertain alternative theories.

Even the normal function of beta-amyloid in the brain is disputed by researchers, as they do not agree on what role it naturally plays in the human body or if it is strictly a marker of Alzeimer’s disease.

A common counter-argument to the amyloid hypothesis is that plaques are found in the brains of many elderly people with normal cognition. Interestingly, some postmortem examinations of people over 90 years old with extraordinary memories have revealed amyloid plaques in their brains to varying degrees — some of them had such a high density that they resembled the most severe cases of Alzheimer’s, and they also had many more neurons than people who had died with Alzheimer’s.

Some researchers believe that beta-amyloid could actually have a protective role.

George Perry, a neurobiologist at the University of Texas at San Antonio, suggests that “beta-amyloid and tau accumulation is actually a protective response to age-related metabolic pressures in the cell,” and is particularly helpful in reducing oxidative stress in the brain (oxidative stress increases with age, which damages the cells).

Several studies have investigated other potential causes of Alzheimer’s disease. One such study was led by researchers at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York who discovered that two strains of a virus called HHV (part of the herpesvirus family) are found in larger quantities in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease. While it is not certain that these two viruses cause the disease (more likely the cause is the combination of virus plus a certain gene variant called APOE), data suggest that infection increases the risk of developing Alzheimer’s. and that people treated with antiviral drugs are ten times less likely to develop Alzheimer’s.

In support of the amyloid theory, however, are genetic findings that link amyloid-related gene problems to the development of early-onset Alzheimer’s disease (in people aged 30 to 65). Down’s syndrome is considered a risk factor, as researchers have found that people with Down’s syndrome have an extra copy of a chromosome that contains the gene coding for an amyloid protein linked to early-onset Alzheimer’s disease.

Other genetic abnormalities may lead to the production of longer variants of beta-amyloid which form plaques more easily, or increase beta-amyloid production and cause somewhat rare cases of early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Multiple family members of one family can carry these gene mutations and increase an individual’s risk of developing early-onset Alzheimer’s.

Supporters of the amyloid theory suggest that earlier trials involving medicines that targeted amyloid plaques were simply flawed. For example, a study of semagacestat, an inhibitor of the production of beta-amyloid proteins, worsened study participants’ cognition; researchers also observed an increase of skin cancer among the participants. This might be due to the fact that semagacestat inhibited the production of other proteins as well, not only beta-amyloid, some of which have important functions in the human body.

The most supported explanation for the failure of these trials that target amyloids is that the medicines are the right medicines, but administered at the wrong point in the progression of Alzheimer’s disease — they are administered too late in the process of forming amyloid plaques, a process which begins decades before symptoms appear.

Michael Murphy, a neuroscientist at the University of Kentucky, notes that “‘we probably already have a drug that could treat Alzheimer’s disease, if we gave it to people in their 50s.’”

There is significant debate about the causes of Alzheimer’s, and experts are not yet aligned — but patients and researchers have caught new wind with aducanumab’s results in one of Aduhelm’s Phase 3 clinical trials.

Aduhelm in clinical trials

Clinical trials take place in four phases:

- Phase 0: The medicine is tested in very small amounts on fewer than 15 participants to ensure it is not harmful and that the trial can continue.

- Phase 1: The medicine is tested on 20 to 80 participants with no underlying health conditions to ensure there are no serious side effects. According to the FDA, approximately 70% of medicines move on to Phase 2.

- Phase 2: The medicine is tested on several hundreds of participants with the condition for which the medicine is intended over a duration of a few months or years to gather information about its effectiveness and side effects. About 33% of medicines move on to Phase 3.

- Phase 3: The medicine is tested on up to 3000 participants with the condition for which the medicine is intended, and can last for several years. The medicine must be proven to be safe and effective. 25-30% of medicines move on to Phase 4.

- Phase 4: This phase involves thousands of participants over many years and takes place after the FDA has approved the medicine. Its purpose is to gather more information about its long-term safety and effectiveness.

Aduhelm in Phase 1

Biogen conducted several clinical trials investigating aducanumab, starting with three Phase 1 trials in 2011 which tested aducanumab in healthy volunteers and in Alzheimer’s disease patients in the US and Japan, working with different doses of aducanumab and placebo. Some patients were enrolled for over 3 years.

In 2016, Biogen published the results of their Phase 1 clinical trial, in which researchers administered monthly intravenous infusions of aducanumab for one year to trial participants with mild Alzheimer's disease. Participants treated with aducanumab had reduced levels of beta-amyloid in the brain and a slowing of cognitive decline as measured by an official Clinical Dementia Rating. Among participants who received aducanumab infusions, Biogen's researchers also recorded a reduction in side effects such as ARIA (amyloid-related imaging abnormalities, e.g. cerebral edema or bleeding in the brain). Biogen found these results to be sufficiently encouraging to proceed to Phase 2.

Aduhelm in Phase 2

Biogen began Phase 2 trials in late 2018 and evaluated the safety of continued dosing of aducanumab, in addition to checking for a reduction of amyloid plaques and a slowing of cognitive decline in participants with early stage and symptomatic Alzheimer’s disease.

Aducanumab failed its primary goal of showing slower cognitive decline at the 12-month mark, but after 18 months of data from the trial were reviewed in a reanalysis, positive effects were observed in one of five doses—the highest dose of aducanumab. The highest dose was shown to reduce the amyloid plaques in the brain, as well as to show positive responses on cognition.

Side effects were observed, as in Phase 1, such as ARIA (amyloid-related imaging abnormalities) in about 10% of all participants, and less than 15% in participants who received the highest doses of aducanumab.

“The 18-month results of the BAN2401 trial are impressive and provide important support for the amyloid hypothesis, said Jeff Cummings, founding director, Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health, in a statement for Biospace.

Aduhelm in Phase 3

After the results of the Phase 2 trial, Biogen conducted two Phase 3 trials, called Engage and Emerge, which enrolled just under 3300 participants with relatively mild Alzheimer’s disease in North America, Australia, Europe, and Asia. Aducanumab was administered once a month at low and high doses by injection into the bloodstream and compared with results of participants who received a placebo.

In March 2019, Biogen stopped the two Phase 3 studies, citing a futility analysis conducted by an independent data monitoring committee which concluded that aducanumab did not appear to be working as intended.

The decision affected 3300 study participants. The protocols for taking part in the study involved frequent and extended visits and included blood draws, MRIs, PET scans, and sometimes spinal taps. Seven months after the stopping of the two studies, Biogen announced that a reanalysis of additional data indicated that at high doses the medicine appeared to reduce cognitive decline.

Biogen wrote in a press release that the additional data consists of results from a subset of patients in the Phase 3 Engage study who received a high dose of aducanumab and experienced significant reduction in cognitive and functional impairments (memory, orientation, language), as well as benefits to activities in daily life (doing household chores, shopping, independently traveling out of the home). Based on these results, Biogen applied for regulatory approval for aducanumab in October 2019 and received it in early June 2021.

Although the Phase 3 clinical trials were not fully conclusive on the therapy’s benefits regarding cognition and function, the FDA concluded that the trials demonstrated that aducanumab, produced under the trade name Aduhelm, can reduce amyloid plaques, which formed the basis for the FDA’s accelerated approval decision.

Trial participant and reporter Phil Gutis wrote for the Being Patient news platform, “I’ve learned through a longitudinal study PET scan that I no longer have any amyloid in my brain. The scan, taken about two years ago as part of the Aging Brain Cohort study at the Penn Memory Center, confirmed my growing inklings that aducanumab was indeed helping me. I began to feel like I was emerging from a constant mental fog … On the negative side, the memories that I’ve lost have not returned.”

Side effects and contraindications of Aduhelm

According to Biogen's Medication Guide, before considering Aduhelm, patients should inform their healthcare providers of all of their medical conditions, including if they:

- are pregnant or plan to become pregnant

- are breastfeeding or plan to breastfeed

Patients should tell their healthcare providers about any medicines they take, including prescription and over-the-counter medicines, vitamins, and herbal supplements.

According to Biogen’s Medication Guide, the main known side effect of Aduhelm is ARIA (amyloid-related imaging abnormalities), such cerebral edema and bleeding in the brain. The other side effects are:

- serious allergic reactions, such as swelling of the face, lips, mouth, or tongue and hives

- headaches

- diarrhea

- confusion/delirium/altered mental status/disorientation

- falls

ARIA is a common side effect that does not usually cause any symptoms, but can be serious. It is most commonly seen as a temporary swelling in the brain that usually resolves on its own over time. At the same time, removing amyloid from the brain also removes amyloid from blood vessels, which can create small spots of bleeding in or on the surface of the brain.

ARIA was observed in 41% of participants in the clinical trials who received aducanumab, compared with 10% of participants who received a placebo.

Although most people with swelling in areas of the brain do not have symptoms, about 30% of people may have mild symptoms, such as:

- confusion

- headaches

- dizziness

- vision changes

- nausea

Daniel Gibbs, retired neurologist and long-term participant in the Aduhelm clinical trials, shared his experience with an extremely rare ARIA side effect:

“I should say first, and this is the dogma which is largely true, that [ARIAs] are usually benign. Most people don’t know they have it. [ARIAs] are only caught on MRI scans where there’ll be little areas of swelling or little tiny areas of iron deposition from bleeding. If people have symptoms from them, they’re usually mild. Headache is the most common one, occasionally confusion.

But almost always, even with symptomatic ARIA, if you stop the drug, they’ll go away in a few months. The drug can be restarted again safely. There have been very few cases, at least that have been discussed by the maker of the drug Biogen, [of] catastrophic ARIA or serious ones, and mine was in that category. [...]

I started to have an increase in headaches. I get headaches not uncommonly so I didn’t really think anything of it, but they became a little more frequent and perhaps a little more severe but still relieved by over-the-counter [medications]. [...]

Then a night or two before Christmas of 2017, I had the worst headache of my life, the kind that we as neurologists would associate with subarachnoid hemorrhage, massive bleeding into the brain. I took my blood pressure and it was sky high and remained high, so I thought I was having a stroke.

I had my wife take me to the emergency room, and by the time I got to our local hospital, I really couldn’t give a coherent history. [...]

But within a few days I was doing a little bit better. My headache went away, but I still had trouble reading. Over the next month, it got a little worse. My MRI scans by that time showed this was ARIA with both the swelling and the bleeding all over my brain. Because it increased, it was felt that it should be treated. I received five doses of high dose steroids and that immediately relieved the headache and confusion. But it took about six months for the swelling in my brain to totally go away.”

In light of these rare but serious potential side effects, patients’ healthcare providers will have to conduct magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans before and during the treatment with Aduhelm to check for ARIA.

Approval of Aduhelm (aducanumab)

On the 7th of June 2021, the FDA granted accelerated approval to Aduhelm (aducanumab) for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease.

Accelerated approval is a type of approval that can be granted to medicines that show a positive therapeutic effect in clinical trials, before all conclusive evidence has been submitted. This can only apply to medicines for serious conditions that fill an unmet medical need; the last medicine approved for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease was approved more than 18 years ago.

Accelerated approval is granted conditionally. FDA is requiring the manufacturer, Biogen, to conduct a new clinical trial. to verify the medicine’s clinical benefit If the trial fails to show benefits, the FDA could withdraw approval of the medicine. Biogen has until 2029 to complete another clinical trial to confirm aducanumab’s benefits for Alzheimer’s patients; experts argue that a third clinical trial, which could be completed in two years, would have been a better option than waiting eight years to find out whether the medicine works, while patients undergo the expensive treatment and hope for the best.

A medical controversy with financial undertones

The FDA’s decision to approve aducanumab has puzzled experts who say there is not enough evidence that Aduhelm is an effective treatment for Alzheimer’s disease. Many of them, including an independent panel, advised the FDA that the available evidence raised significant doubts that aducanumab could slow cognitive decline and debated whether positive results from only one of the two Phase 3 studies is sufficient basis for FDA approval.

Shortly after the approval, three scientists resigned in protest from the independent committee that advised the FDA on the treatment, citing the lack of convincing evidence. They also criticised the FDA’s decision to approve aducanumab for anyone with Alzheimer’s, despite the trial being conducted on early-stage Alzheimer’s, and the acceptance of the theory that reducing amyloid plaque would actually slow their cognitive symptoms (despite the scientific community’s misalignment over its validity).

The FDA’s decision to approve aducanumab under these conditions could have several ramifications.

- Other medicines that target amyloid plaques, such as Eli Lilly's donanemab, could get approved faster than previously forecasted, spurring interest in pharma companies to invest in Alzheimer’s medicines or continue their involvement with existing trials.

- The FDA’s decision has created a perception of regulatory flexibility that could incentivize other biotech companies to develop medicines for rare conditions, a drive that has deflated after a long string of clinical trial failures, particularly in the 18 years between Alzheimer’s treatments approvals.

- The medicine is quite costly at $56,000 per year, which means that private health insurance rates might increase as insurers will be expected to pay for it, and it will increase the burden on taxpayers as part of Medicare (the US national health insurance). Some say it could be “devastating” for Medicare, not only due to its base costs, but also because treatment with Aduhelm requires patients to have earlier diagnoses with spinal taps to detect amyloid and constant monitoring with MRIs (among others), which significantly increases the costs and puts pressure on medical systems.

The approval is also seen as a windfall for Biogen, as their shares rose more than 50%, while shares of Japanese partner Eisai Co climbed 56%. Aduhelm could potentially reap some $10 billion in sales, analysts predict, considering that in the US alone there are 6 million people diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. The medicine is important to Biogen’s growth as competition has hurt the sales of their medicines — Tecfidera for multiple sclerosis (MS), and Spinraza for spinal muscular atrophy (SMA).

Spinraza is another medicine in Biogen’s portfolio with a high price tag, at a list price of $750,000 for the initial year of treatment and $375,000 per year thereafter.

Not everyone is critical of the FDA’s decision to approve Aduhelm

Since Alzheimer’s is a progressive disease, patients need treatment sooner rather than later. The news of the FDA’s decision has given many new hope, either that the treatment works for themselves or their loved one, or that it will spur other companies into action to develop other Alzheimer’s treatments.

Patient advocacy groups had vigorously pushed for approval because there are only six other treatments available for the debilitating disease, which only address symptoms for a matter of months. In November 2020, the FDA’s advisory committee voted against the approval of Aduhelm, which sparked anger and then action among the Alzheimer’s Association, who then campaigned to express their support for the drug’s potential and to emphasize the need for hope and progress.

In January 2021, the FDA and patient groups met in a listening session where patients, caregivers, clinicians, and advocates were in favor of the treatment, arguing among other things that patients cannot afford to wait any longer for a treatment.

FDA Office of New Drugs Director Peter Stein confirmed during a press conference that patient opinions played a role. He said the FDA “heard very clearly from patients that they’re willing to accept some uncertainty to have access to a drug that could provide meaningful benefit in preventing the progression of this disease, which as we all know, can have very devastating consequences.”

Patrizia Cavazzoni, the acting director of the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said during the same press conference that “the data support patients and caregivers having the choice to use this drug.”

“This FDA drug approval ushers in a new era in Alzheimer's treatment and research,” said Maria Carrillo, Ph.D, the Alzheimer’s Association’s chief science officer. “History has shown us that approvals of the first drug in a new category invigorates the field increases investments in new treatments and encourages greater innovation.”

When will Aduhelm be approved in Europe?

Alzheimer’s disease is rapidly rising as one of the century’s major medical, economic and social crises — and one that is difficult to detect early on, especially considering the lack of specialists in Europe who can confirm a diagnosis. In Europe alone, as of 2018, 9.7 million people suffer from Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia; by 2030, the number of patients is projected to rise to 14 million, creating a dire need for effective treatments.

Aduhelm has not yet been approved outside of the United States. Biogen has filed for regulatory review in the European Union in October 2020, as well as in Japan, Canada, Australia and Brazil at the end of the year 2020.

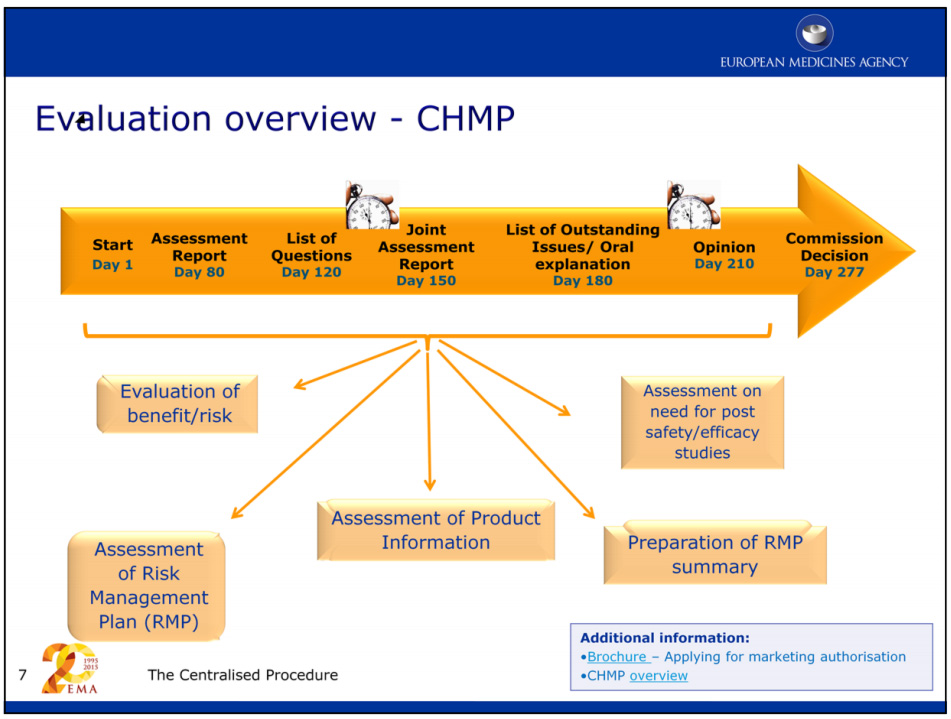

According to the European Medicines Agency (EMA), the assessment of a marketing authorisation application for a new medicine usually takes around a year, less if the medicine developer is granted Accelerated Assessment.

In March of this year, Biogen’s $2 billion manufacturing facility in Switzerland received a Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) license from the Swiss Agency for Therapeutic Products (Swissmedic). Biogen plans to seek FDA approval to produce Aduhelm in the Swiss facility in late 2021 and expects to supply the medicine to more than 1 million patients per year.

Accessing Aduhelm outside of the United States

Aduhelm is currently FDA approved and available for United States residents — and there are regulations that allow for medicines to be imported in countries where they are not currently approved.

Patients with life-threatening or debilitating diseases have the right to access, purchase, and import medicines with the help of their treating doctors.

Patients and their doctors can do this on the compassionate use or named patient import regulations basis, a legal exception of the general rule that a medicine can normally only be accessed after market authorisation/approval (whatever wording we use) in the country where the patient lives. This exception allows patients to in a legal, ethical and safe way access and get medicines that are not yet approved in their country.

Read more about the “named patient basis” here (EMA).

everyone.org are committed that patients and their treating physicians may have access to any medicine available throughout the world for best possible treatment. We operate 100% compliantly within the regulations in your country if you are outside of the United States. If you want to read more details, access the medicine or would like to contact our support team you can do that here.

How much does Aduhelm cost?

Biogen has announced that the Aduhelm cost at the maintenance dose (10 mg/kg) for an average patient would be $56,000 per year. That does not include the testing that patients have to do prior to the treatment and during the treatment.

Biogen has received criticism regarding the high price of the medicine per year.

The nonprofit Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER), which analyzes medicine prices, indicated that a fair annual price would range from $2,500 to $8,300 per patient each year. In a statement, ICER said the FDA's approval failed to protect patients, and Biogen could collect more than $50 billion per year "even while waiting for evidence to confirm that patients receive actual benefits from treatment.”

Biogen CEO Michel Vounatsos has responded to criticism by asserting that the price of the drug is justified by the value it will bring to patients and a society less burdened by Alzheimer’s, and that the price is a reflection of “two decades of no innovation.” “It is time to invest in treatment,” he added.

At everyone.org, we can not influence the price set by Biogen. We are able to help patients access Aduhelm at the following prices:

- €1,958.58 for one vial of 170 mg/1.7 mL (100 mg/mL)

- €3,046.68 for one vial of 300 mg/3 mL (100 mg/mL)

Make an enquiry here for further information.

Upcoming treatments for Alzheimer’s disease

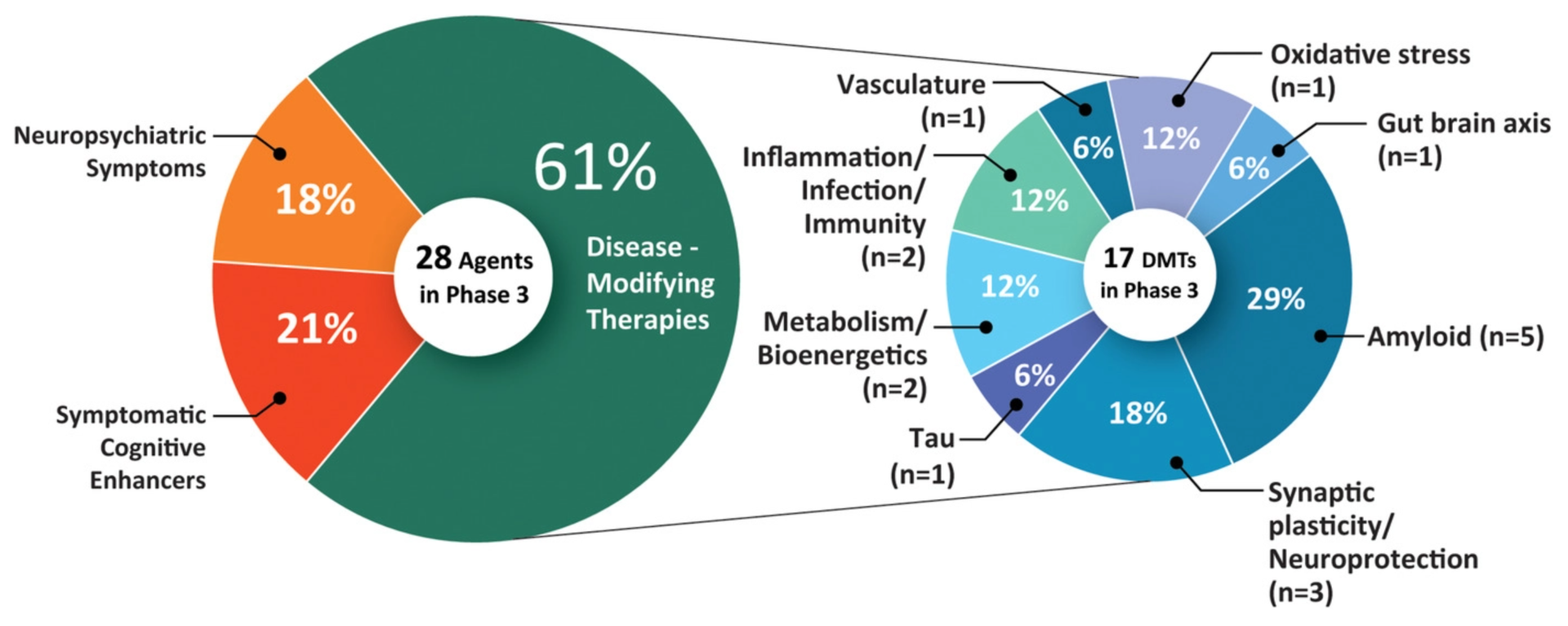

A study published in May 2021 shows that there are currently 126 treatments in clinical trials for Alzheimer’s disease. 82.5% of them target disease modification, 10.3% enhance cognition, and 7.1% focus on relieving neuropsychiatric symptoms.

- Phase 3 trials: 28 treatments (including aducanumab)

- Phase 2 trials: 74 treatments

- Phase 1 trials: 24 treatments

The treatments in Phase 3 trials are most likely to be approved in the coming year.

Lecanemab

Operating in a similar way as aducanumab (triggering the immune system to remove beta-amyloid plaques), the monoclonal antibody lecanemab shows promise, according to the reports published, and has moved into Phase 3 clinical trials.

Gantenerumab

Gantenerumab binds to beta-amyloid, particularly to plaques of beta-amyloid compared to individual beta-amyloid that is circulating in the blood. It is thought to dissolve amyloid plaques and remove beta-amyloid by stimulating phagocytosis, a process where a cell takes a certain molecule inside itself and digests it. Previous clinical studies of gantenerumab showed that it reduced beta-amyloid plaque people with the more common form of Alzheimer’s that is not directly caused by gene mutations. It continues to be studied in two large global Phase III studies.

Solanezumab

Solanezumab is an antibody that aims to “clean” beta-amyloid from the blood and cerebrospinal fluid, thereby preventing plaque formation. Benefits were reported in participants who took part in the full three and a half year period of the trials, and less so in participants who joined later, so there is still more to learn about its effects.

Donanemab

Donanemab seems to be another promising upcoming medicine for the treatment of Alzheimer’s. It is being tested by Eli Lilly and Company, which plans to enroll 1500 participants in a large study in order to confirm results from its smaller study; this previous study lasted 76 weeks and included 257 patients, and, according to the reports, showed that donanemab significantly slowed the progress of Alzheimer’s disease.

Others

Saracatinib is an experimental compound that acts as an inhibitor of a protein called Fyn kinase which aids the formation of beta-amyloid plaques. A study conducted on mice showed that saracatinib, by inhibiting Fyn kinase, was effective in reversing memory loss in mice. Fyn kinase inhibition may prevent or delay disease progression.

Researchers at Salk Institute for Biological Studies in California are studying a chemical called fisetin and developed a version of fisetin called CMS121, which they found to be effective in slowing the loss of brain cells. More research is required before a medicine is ready for approval.

Regarding Aduhelm’s recent approval, Maria Carrillo, Chief Science Officer for the patient-advocacy group Alzheimer’s Association in Chicago, USA, said in a statement for Nature: “We are hopeful, and this is the beginning — both for this drug and for better treatments for Alzheimer’s.”

"All we really are is our thoughts and our brain." – Sandy, former dentist and assistant professor and Alzheimer’s patient.

At everyone.org, we are convinced that science moves the human race forward and improves or even saves lives. Alzheimer’s disease is jeopardizing the quality of life of many. We encourage scientists dedicated to finding a (part of the) solution to persevere and we are looking forward to treatments under development showing promising results to be approved and become accessible for Alzheimer’s patients around the world within the next 3 years.